Failing Grades: States’ Responses to COVID-19 in Jails & Prisons

By Emily Widra and Dylan Hayre Tweet this

June 25, 2020

When the pandemic struck, it was instantly obvious what needed to be done: take all actions possible to “flatten the curve.” This was especially urgent in prisons and jails, which are very dense facilities where social distancing is impossible, sanitation is poor, and medical resources are extremely limited. Public health experts warned that the consequences were dire: prisons and jails would become petri dishes where, once inside, COVID-19 would spread rapidly and then boomerang back out to the surrounding communities with greater force than ever before.

Advocates were rightly concerned, given the long-standing and systemic racial disparities in arrest, prosecution, and sentencing, that policymakers would be slow to respond to the threat of the virus in prisons and jails when it was disproportionately poor people of color whose lives were on the line. Would elected officials be willing to take the necessary steps to save lives in time?

When faced with this test of their leadership, how did officials in each state fare? In this report, the ACLU and Prison Policy Initiative evaluate the actions each state has taken to save incarcerated people and facility staff from COVID-19. We find that most states have taken very little action, and while some states did more, no state leaders should be content with the steps they’ve taken thus far. The map below shows the scores we granted to each state, and our methodology explains the data we used in our analysis and how we weighted different criteria.

For the details of each state’s score, see the appendix. *This report does not provide a grade to Illinois because some of the relevant data is the subject of pending litigation. |

The results are clear: despite all of the information, voices calling for action, and the obvious need, state responses ranged from disorganized or ineffective, at best, to callously nonexistent at worst. Even using data from criminal justice system agencies — that is, even using states’ own versions of this story — it is clear that no state has done enough and that all states failed to implement a cohesive, system-wide response.

In some states, we observed significant jail population reductions. Yet no state had close to adequate prison population reductions, despite some governors issuing orders or guidance that, on their face, were intended to release more people quickly. Universal testing was also scarce. Finally, only a few states offered any transparency into how many incarcerated people were being tested and released as part of the overall public health response. Even in states that appeared, “on paper,” to do more than others, high death rates among their incarcerated populations indicate systemic failures.

The consequences are as tragic as they were predictable: As of June 22, 2020, over 570 incarcerated people and over 50 correctional staff have died and most of the largest coronavirus outbreaks are in correctional facilities. This failure to act continues to put everyone’s health and life at risk — not only incarcerated people and facility staff, but the general public as well. It has never been clearer that mass incarceration is a public health issue. As of today, states have largely failed this test, but it’s not too late for our elected officials to show that they can learn from their mistakes and do better.

Methodology & Scoring

Composite score:

The final composite score for each state equals the total of all points received ranging from zero to 485. To make the scores easier to read, we then divided the final number of points by 4.85 to give each state a grade on the scale of 0-100. Because every state scored so poorly, we decided to adjust the traditional school grading scale down

to create some meaningful differentiation in the scores, and to better identify the states that, despite falling far short of these minimum standards, did make some notable strides. This differentiation and specificity is important because this report, while assessing what has happened thus far, should also help create a blueprint for what states can do to save lives as the pandemic continues.

How we graded and what distinguishes a higher score:

To assess the degree to which each state has responded to the COVID-19 pandemic and the particular threat of viral infection behind bars, we looked at whether:

- The state Department of Corrections provided testing and personal protective equipment (PPE) to correctional staff and the incarcerated population. (maximum 65 points)

- The state reduced county jail populations and state prison populations. (maximum 300 points)

- The governor issued an executive order — or the Department of Corrections issued a directive — accelerating the release from state prisons of medically vulnerable individuals and/or those near the end of their sentence. (maximum 60 points)

- The state published regularly updated, publicly available data on COVID-19 in the state prison system. (maximum 60 points)

Recognizing that no metrics can account for all differences between states, including the fact that the virus reached some states earlier than others, we then deducted points from the final scores of states that have had COVID-19 deaths in their state prisons. Information regarding testing, personal protective equipment (PPE), and regularly updated, publicly available data was collected from the states’ Department of Correction websites in early June 2020. Some states may have implemented more widespread testing — or are providing PPE to all incarcerated people — but if that information is not clearly shared on their website at the time of our data collection, we could not include it in our scoring.

Has the Department of Corrections provided comprehensive testing and personal protective equipment (PPE) to correctional staff and the incarcerated population? (maximum 65 points)

The easiest steps states can take to prevent COVID-19 deaths behind bars are to provide testing and protective equipment to incarcerated people and prison staff.

These measures will also slow the spread of COVID-19 into the communities surrounding prisons.

Only five states — Massachusetts, Michigan, Tennessee, West Virginia, and Vermont — were awarded 20 points for completing comprehensive testing of the population in state prisons. Three states — New Mexico, Massachusetts, and West Virginia — completed comprehensive testing of all correctional staff and were awarded 15 points. States that are in the process of comprehensive testing of incarcerated people and correctional staff were awarded 5 points for testing of incarcerated people and 5 points for testing of correctional staff.

We also awarded states 15 points for providing personal protective equipment (PPE) to all staff, and 15 points for providing PPE to all incarcerated people. Most, if not all, PPE in the correctional setting, especially for confined populations, consists of non-surgical masks. States received 5 points for only providing PPE to some incarcerated people and some staff (i.e. incarcerated people who were exposed to someone who tested positive, or only intake unit staff). Only three states — Florida, Rhode Island, and North Dakota — do not have information about providing PPE to incarcerated people.

Because we wanted to keep our scoring consistent across states, we chose to utilize the data provided by individual Departments of Correction on their websites. To the degree that states are not following their own policies mandating access to face masks and other PPE, the reality behind bars may be worse.

If there was no reliable evidence that states were providing those tests or PPE, we awarded states zero points.

How we awarded points for testing and provision of personal protective equipment (PPE). For the details on how your state scored, see the appendix. | ||||

COVID-19 Testing | ||||

No testing or limited testing | Commitment to full testing | Full testing completed | Maximum points available for testing | |

Correctional staff | 0 points | 5 points | 15 points | 35 points |

Incarcerated population | 0 points | 5 points | 20 points | |

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | ||||

No PPE or limited PPE | Commitment to full PPE for all | PPE provided to all | Maximum points available for PPE | |

Correctional staff | 0 points | 5 points | 15 points | 30 points |

Incarcerated population | 0 points | 5 points | 15 points | |

How much has each state reduced incarcerated populations in both local county jails and state prisons? (maximum 300 points)

The high rate of coronavirus infections and deaths in correctional facilities is due to their population density: incarcerated people frequently have to sleep, eat, and shower within a few feet of one another, and share common amenities such as phones. Public health experts have been clear that reducing facility density — allowing people to return home — is the most critical and necessary step to save lives. States that have reduced the population density in correctional facilities — starting by releasing old and frail people especially vulnerable to COVID-19 — have slowed the spread of the virus more effectively and saved more lives.

Jails

Jail population mitigation needs to be a key part of the national response to COVID-19. If jails fail to drastically reduce their populations, COVID-19 could claim up to 100,000 more people than the current projections. In mid-April, an epidemiological study conducted by the ACLU and university researchers found that keeping people out of jail saves lives — both inside the jail and in the surrounding communities. And while nationally jail populations have decreased much more than state prison populations, not all states are taking this call to decarcerate jails seriously. We awarded one point for each percentage point that each state reduced its median jail population.

The median jail population reductions in each state vary drastically from a 42% reduction in Arkansas to only 2% in Texas, and some states appear to have had increases in jail populations.

To calculate the median jail population change, we analyzed data collected from the NYU Public Safety Lab, supplemented by data collected by the Vera Institute of Justice, on population changes from January 2020 to June 1, 2020.

For Massachusetts jail data, we analyzed the data published by the ACLU of Massachusetts for all counties. West Virginia and Maryland jail data were provided by ACLU of West Virginia and ACLU of Maryland. The jail population data for the ten largest counties in Missouri came from the ACLU of Missouri, and for the 35 other counties included in this report the data was collected by the NYU Public Safety Lab.

The jail data used for this report has population data over time for over 1,200 county jails, with a nationwide median population reduction of about 20%.

Prisons

The public health response cannot end in jails — states must also address their prisons, with a combined and dense population of 1.3 million. Reducing the number of people who are currently incarcerated will limit the burdens people face due to incarceration or supervision that place them at elevated risk of being affected by the coronavirus pandemic. We awarded two points for each percentage point that a state reduced its prison population.

We analyzed the change in state prison population counts from the start of 2020 (using data from either December 31, 2019 or January 1, 2020) and four months later (using data from April 30, 2020 or May 1, 2020).

We note that state Departments of Correction have been announcing plans to reduce their prison populations — by halting new admissions from county jails, increasing commutations, and releasing people who are medically fragile, elderly, or nearing the end of their sentences — but our analysis finds that the resulting population changes have been small, at about only 5%.

This report collected data from 49 states. We note that we awarded Maryland zero points in section for the prison population reduction efforts that may or may not have taken place in this study period because that state did not provide April/May data to the Vera Institute of Justice and failed to respond to two requests by the Prison Policy Initiative for April/May data. All other states provided population data to either the Vera Institute of Justice or the Prison Policy Initiative.

How we awarded points for jail and prison population reductions. For the details on how your state scored, see the appendix. | ||

Points for each | Maximum points available | |

Jails | 1 | 100 |

Prisons | 2 | 200 |

Has the governor issued an executive order to halt jail admissions or to mandate the release of medically vulnerable individuals or those who are nearing the end of their sentence? Has the DOC issued a statewide directive to release medically vulnerable individuals or those who are nearing the end of their sentence? (maximum 90 points)

Some governors and Departments of Correction have led their state’s criminal justice systems in a coordinated response to the pandemic in jails and prisons.

Others have left it up to local criminal justice stakeholders — police, prosecutors, judges, sheriffs, and supervision agents — to implement their own individual responses to COVID-19, leading to inevitable delays, confusion, and inefficient allocation of resources.

In some states — such as Colorado, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Washington — release orders from the governor or the Department of Correction authorized the release of both medically vulnerable people and those nearing the end of their sentences.

Other governors issued executive orders that called for the release of either the medically vulnerable or those nearing the end of their sentence. Every executive release order analyzed contained specific offense criteria, most often excluding those charged with felonies, “violent offenses,” or sexual offenses. Governors in a number of states — including Colorado — that received points for executive orders have since let these executive orders expire.

If any states had issued an order that would release all people who were determined to be medically vulnerable and/or nearing the end of their sentence regardless of offense type, we would have awarded them up to 60 points; but no states took these essential steps.

How we awarded points for executive orders and Department of Correction directives. For the details on how your state scored, see the appendix. | ||||

Order for halting jail admission | Order for releasing medically vulnerable | Order for releasing people near end of sentences | Maximum points available | |

No order exists | 0 points | 0 points | 0 points | 90 points |

Partial order or guidance | 10 points | 10 points | 10 points | |

Complete order | 30 points | 30 points | 30 points | |

Partial release orders — release orders that exclude people based on offense type — or non-mandatory guidance were awarded 10 points, and states with no executive or DOC release orders received 0 points (out of 50 states, only 20 states received any points for executive release orders). States also received 10 points if they suspended incarceration for technical violations of community supervision, which occurred in Alabama, Michigan, and Washington.

States with executive orders that put a moratorium on all jail admissions were awarded 30 points (no states received all 30 points).

States with executive orders or Department of Correction orders that halted some admissions to jails, for example halting jail bookings for certain misdemeanors or technical violations of probation or parole, received 10 points. States without orders addressing jail admissions received zero points.

Does the state or Department of Corrections provide publicly available, regularly updated data on COVID-19 behind bars? Is this data disaggregated by race? (maximum 30 points)

COVID-19 is killing more Black people and more people of color across the nation. And in a criminal justice system that disproportionately locks up Black people, the threat of the pandemic is heightened. Because of this, we need to know — and address — how COVID-19 is affecting people behind bars in order to slow the continued spread of the pandemic.

To assess states’ responses to COVID-19 behind bars in the appropriate context, it is necessary to know how many incarcerated people and staff in each state have already contracted the virus and how fast it is spreading. We awarded points to states that have published this data for state prisons. States providing frequently updated, accessible, and comprehensive correctional data on COVID-19 received 15 points; those providing more limited data received 5 points.

We awarded additional points to states that have provided data disaggregated by race — data that can help us assess whether prison and jail officials have taken Black individuals’ health complaints less seriously than those of incarcerated white people and staff. (Black people are overrepresented in incarcerated populations and among correctional staff, and the disproportionate number of coronavirus deaths among people of color in the general public is already well documented.) States providing data that is disaggregated by race received 15 points. If only some sections of a state’s correctional data were disaggregated by race, we awarded 5 points.

There are two states with limited correctional COVID-19 data — New Mexico and Wyoming — and those states received only 5 points. 12 states offer publicly available and regularly updated data and received 15 points.

Only eight of those states’ data includes specifics on race; and those states — Delaware, Maine, Michigan, Missouri, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Vermont, and West Virginia — received an additional 15 points.

How we awarded points for Departments of Corrections’ state prison COVID-19 data availability. For the details on how your state scored, see the appendix. | |||

COVID-19 data availability | Disaggregated by race | Maximum points available | |

No data | 0 points | 0 points | 30 points |

Some data | 5 points | 5 points | |

Full data | 15 points | 15 points | |

Points deducted for COVID-19 deaths in state prisons

In recognition of the fact that human life is precious and that policy decisions have real life consequences, we deducted points for deaths in state prison custody. States should have immediately taken the common sense actions described in the report, but they largely have not, even months later. And even the states that took positive steps did so much later than they should have, raising the human cost.

For that reason, we deducted from the final score of each state 1 point for every 5 prison deaths per 10,000 people in the state’s prison system. (By tying the deductions to the number per 10,000 we account for vastly different prison population sizes in different states.)

We considered weighting this outcome more heavily, but we ultimately did not do so for several reasons. First, the difference in death rates between states is in part the result of policy differences and in large part the temporary result of the fact that the virus started spreading in some places earlier than others. If we weighted this factor more heavily, we’d be giving a pass to states that took little action and saw their deaths predictably spike after publication of this report. Second, even while comparing prison death rates — rather than counts — a single death in any of the smaller states still has an outsized impact on the overall scoring. Third, as this report has argued, prison deaths are just one part of the human cost that we do not, at this time, have a way to calculate. In particular, we do not yet have a reliable way to calculate all of the other ways in which criminal justice failures lead to deaths from COVID-19, including: undisclosed COVID-19 deaths in prisons, deaths from other causes in incarcerated people who were weakened by COVID-19, or deaths from community spread that was first incubated in the state’s prisons. For that reason, for a report written while the pandemic is still in its early stages, we chose to include these deaths and challenge all states to do far better. The final history will not be written until long after the pandemic ends, but elected officials need to be on notice that history is watching.

Acknowledgements

The ACLU thanks Charlotte Resin, Brandon Cox, Raymond Gilliar, Neil Shovelin, Ari Rosmarin, Kary Moss, Udi Ofer, Taylor Pendergrass, and ACLU Affiliates and staff for their assistance and support in compiling this report.

About the authors

Emily Widra is a Research Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative. As the organization’s expert on the criminal justice system’s responses to the pandemic, she has published several short and impactful reports about the criminal justice system and the coronavirus. She curates the Prison Policy Initiative’s virus response page, tracking the criminal justice policy changes that states and counties have made in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Her previous research also includes analyses of mortality in prisons and the combined impact of HIV and incarceration on Black men and women.

Dylan Hayre is a Campaign Strategist at the ACLU’s Justice Division where he leads the ACLU’s advocacy work on clemency and death penalty repeal. He has also been helping spearhead and coordinate the organization’s efforts to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic in partnership with many of the ACLU Affiliates across the country. Prior to joining the ACLU, Dylan served as the Senior Policy Advisor at JustLeadershipUSA where he strengthened and advised on their advocacy and policy work in numerous jurisdictions. Before that, he was a prosecutor, litigator, and campaign organizer in his home state of Massachusetts.

About the Prison Policy Initiative

The non-profit non-partisan Prison Policy Initiative was founded in 2001 to expose the broader harm of mass criminalization and spark advocacy campaigns to create a more just society. It sounded the national alarm about the threat of coronavirus to jails and prisons with its March 2020 report No need to wait for pandemics: The public health case for criminal justice reform. The organization’s data-driven coverage of the pandemic behind bars continues to advance the national movement to protect incarcerated people from COVID-19

About the ACLU Campaign for Smart Justice

The ACLU’s Campaign for Smart Justice is an unprecedented, multiyear effort to cut the nation’s jail and prison populations by 50% and challenge racial disparities in the criminal justice system. The Campaign is building movements in all 50 states for reforms to usher in a new era of justice in America.

Footnotes

1.

Composite score | Letter grade |

0-6.9 | F- |

7-13.9 | F |

14-20.9 | F+ |

21-27.9 | D- |

28-34.9 | D |

35-41.9 | D+ |

42-48.9 | C- |

49-55.9 | C |

56-62.9 | C+ |

63-69.9 | B- |

70-76.9 | B |

77-83.9 | B+ |

84-90.9 | A- |

91-100 | A |

100 | A+ |

2. After request from the ACLU of New Hampshire, and to protect incarcerated people from COVID-19, the New Hampshire Department of Correction began publishing on its website daily metrics on the status of COVID-19 inside the prisons; it made facial masks available to all incarcerated people; and reinstated the provision of alcohol-based hand sanitizer, previously prohibited inside the prison due to alcohol content. The Commissioner of Corrections also streamlined the process for administrative-home-confinement (AHC), resulting in a 100% increase in the number of people released on AHC since March, according to the ACLU-NH. And even while this was not factored into our scoring metrics, it should be noted that the DOC has also instituted a policy that it will not admit people admit people from county facilities where there has been a positive COVID-19 case amongst the jail population and that testing is widely available, actions that have been applauded by the ACLU-NH.

3. For example, California has statewide policies mandating access to face masks, but reports from inside state prisons suggest that access and use of face masks are limited. Additionally, this section scores PPE policies in state prisons, but access to PPE is also critical in jails as well. The ACLU of Southern California and Northern California recently filed a statewide lawsuit with declarations from 13 counties saying that PPE was not consistently provided to incarcerated people or worn by the staff in jails.

4. Not all states have taken these steps to reduce their prison populations voluntarily. For example, Hawai’i (which has a combined prison and jail system), began to reduce the incarcerated population following a lawsuit that resulted in court orders from the Hawai’i Supreme Court to expedite early releases and provide appropriate personal protective equipment.

5. The median jail population change may be different from the average or total statewide jail population, but by using the median, we are able to show population change across all states, even those for which only some counties have jail data available.

6. Jail population data was only available for 5 of the 27 county jails in South Dakota and the median jail population change in those jails reflected an increase of 3.7%. It is possible that with data for more counties, the median jail population change would look different, but based on the available data, South Dakota was awarded negative points because their jail population went in the wrong direction. In New Hampshire, jail data was only available for two small counties, and we therefore did not include any jail population changes in the New Hampshire score (New Hampshire was awarded 0 points for jail population changes).

7. In order to present a sample that was as representative of the state jail system as possible, we included all jails with available data in our analysis. We only excluded jails with pre-pandemic populations under 10 people, as the movement of a small number of people in and out of these small jails can swing the state’s median percentage of jail reduction in misleading ways. (Previous Prison Policy Initiative briefings on jail reductions during the pandemic excluded jails with populations under 350 because we wanted to lessen the impact of small daily population variations in small jails looking more dramatic than they are. Upon a deeper analysis of this expanded dataset, we conclude that excluding these smaller facilities would not measurably change the results, so we kept this dataset as expansive as possible.) In general, we found that large county jail populations had larger percentage drops than smaller county jails. There are some states for which there is only limited jail population data available — data is only available for less than 15% of the counties in Nebraska, South Dakota, and Michigan — so it is possible that the scores for these states could be higher with a more complete sample.

8. Readers may notice that this median jail population reduction is different than the 31% published last month in the Prison Policy Initiative’s May 14th report, While jails drastically cut populations, state prisons have released almost no one. Although it is difficult to identify exactly what accounts for this difference and when the changes started, we know that some jurisdictions — including Philadelphia — have returned to their pre-pandemic policing practices (which leads to an increase in arrests and jail bookings).

9. State prison population counts retrieved from the Vera Institute for Justice’s report, People in Prison 2019, which published population counts as of April 30, 2020 or May 1, 2020 for 41 states. The Prison Policy Initiative updated this data with prison populations as reported by state Departments of Correction for Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, New Mexico, South Dakota, Tennessee, Virginia, and Washington. Washington prison population data used for this analysis was retrieved from DOC Fact Cards published on December 31, 2019 and March 31, 2020. The Washington Department of Corrections provided the Prison Policy Initiative with data for April 30, 2020, stating that there were 16,531 people in state prison, but because that population count excludes people held for technical violations, we could not compare it to the December 2019 data.

10.Release orders issued by governors and Departments of Correction were compiled by the Prison Policy Initiative based on the Council of State Governments’ executive orders tracking tool.

11. Colorado: Temporarily Suspending Certain Regulatory Statutes Concerning Criminal Justice (D 2020 016); Pennsylvania: Order of the Gov. of Penn. Regarding Individuals Incarcerated in State Correctional Institutions; Virginia: COVID-19 Response Inmate Early Release Plan (from DOC); and Washington: Emergency Commutation in Response to COVID-19 and 20-50 Reducing the Prison Population.

12. For example, in California, Governor Newsom issued an executive order on March 24, 2020 which suspended admissions to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation state prison system. Shortly after this executive order, the CDCR paroled or released to community supervision approximately 3,500 people who were within 60 days of the end of their terms and met specific offense criteria. However, all of those 3,500 people were already scheduled to be paroled in April or May prior to the pandemic, indicating that these releases would have minimal impact on the long-term planning that is necessary to combat the spread of COVID-19 in prisons.

States that took similar steps, including Maine, Virginia, and Wisconsin, would certainly see subsequent prison population reductions. For the purposes of assessing the whole criminal justice system’s response, we only scored executive orders and Departments of Correction initiatives to halt jail admissions in this section. We did not award or subtract points for orders that only halted admissions to state prisons.

13. Not all state Departments of Corrections offer this data voluntarily. For example, the Massachusetts Department of Correction data was compiled and released only after an opinion on April 3rd, 2020 by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS) v. Chief Justice of the Trial Court, SJC-12926.

Ten key facts about policing: Highlights from our work

Police disproportionately target Black and other marginalized people in stops, arrests, and use of force; and are increasingly called upon to respond to problems, such as homelessness, that are unrelated to public safety.

by Wendy Sawyer, June 5, 2020

Many of the worst features of mass incarceration — such as racial disparities in prisons — can be traced back to policing. Our research on the policies that impact justice-involved and incarcerated people therefore often intersects with policing issues. Now, at a time when police practices, budgets, and roles in society are at the center of the national conversation about criminal justice, we have compiled our key work related to policing (and our discussions of other researchers’ work) in one briefing.

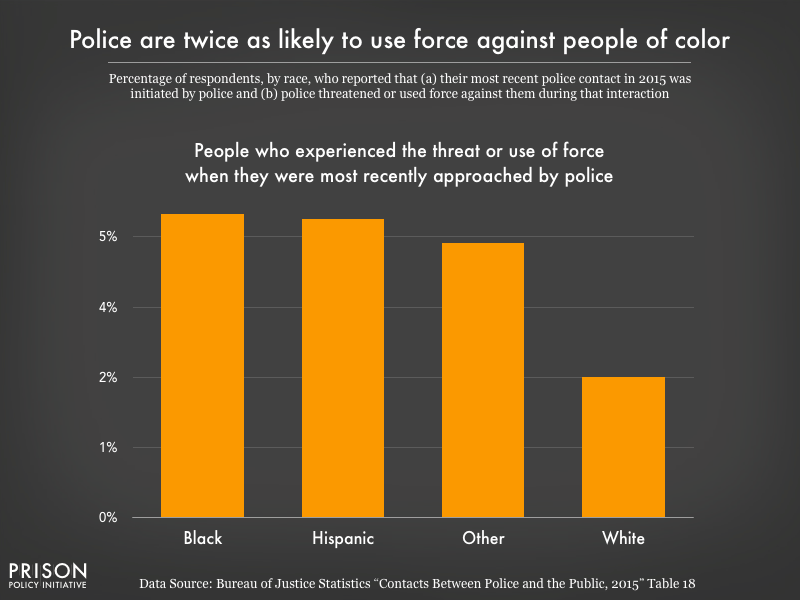

The scale of police use of force is an important fact in and of itself, made more troubling by the racial disparities evident in police stops and use of force. In a national survey, Black respondents were more likely to be stopped by police than white or Latinx respondents, and both Black and Latinx respondents were more likely to be stopped multiple times over the course of a year than white respondents. The survey also showed that when they initiated a stop, police were twice as likely to threaten or use force against Black and Latinx respondents than whites. These disparate experiences have predictable effects on public trust in police: white respondents were more likely to view police use of force as legitimate and more likely to seek help from police than were people of color.

The scale of police use of force is an important fact in and of itself, made more troubling by the racial disparities evident in police stops and use of force. In a national survey, Black respondents were more likely to be stopped by police than white or Latinx respondents, and both Black and Latinx respondents were more likely to be stopped multiple times over the course of a year than white respondents. The survey also showed that when they initiated a stop, police were twice as likely to threaten or use force against Black and Latinx respondents than whites. These disparate experiences have predictable effects on public trust in police: white respondents were more likely to view police use of force as legitimate and more likely to seek help from police than were people of color.

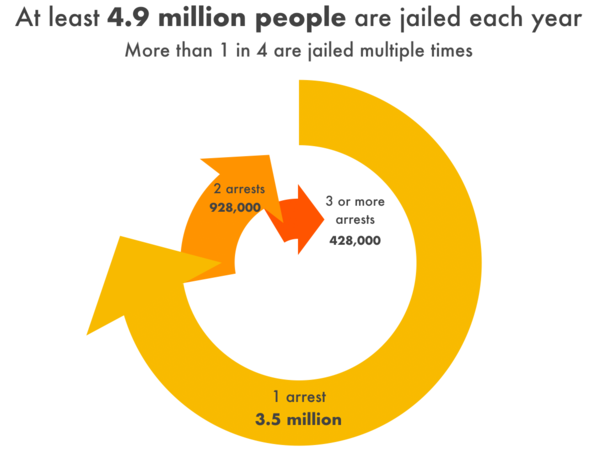

2. Over 4.9 million people are arrested each year.

In all, there are over 10 million arrests in the U.S. each year, but many people are arrested multiple times per year. From responses to a national survey, we estimate that at least 4.9 million unique individuals are arrested and jailed each year, and at least one in four of those individuals are arrested more than once in the same year. The massive scale of these police responses means that there are millions of opportunities each year for police-civilian encounters to turn violent or fatal, and an estimated 77 million people are now saddled with a criminal record.

In all, there are over 10 million arrests in the U.S. each year, but many people are arrested multiple times per year. From responses to a national survey, we estimate that at least 4.9 million unique individuals are arrested and jailed each year, and at least one in four of those individuals are arrested more than once in the same year. The massive scale of these police responses means that there are millions of opportunities each year for police-civilian encounters to turn violent or fatal, and an estimated 77 million people are now saddled with a criminal record.

3. Most policing has little to do with real threats to public safety: the vast majority of arrests are for low-level offenses. Only 5% of all arrests are for serious violent offenses.

The “massive misdemeanor system” in the U.S. is an important but overlooked contributor to overcriminalization and mass incarceration. For behaviors as benign as jaywalking, sitting on a sidewalk, or petty theft, an estimated 13 million misdemeanor charges sweep droves of Americans into the criminal justice system each year (and that’s excluding civil violations and speeding). And while misdemeanor charges may sound like small potatoes, they carry serious financial, personal, and social costs, especially for defendants but also for broader society, which finances the enforcement of these minor violations, the processing of these court cases, and all of the unnecessary incarceration that comes with them.

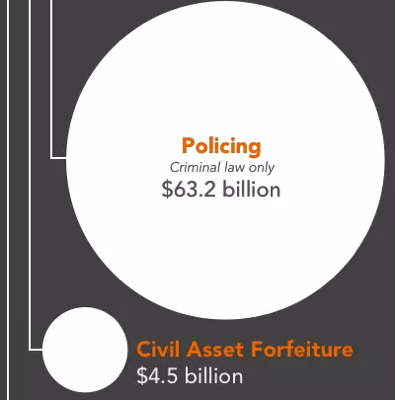

4. Policing criminal law violations costs taxpayers over $63 billion each year.

Policing costs the public $126.4 billion per year, nationwide. In our report about the fiscal costs of mass incarceration to the government and families of justice-involved people, we used only half of that figure – $63.2 billion – because only about half of police work is devoted to criminal law enforcement. The other half is spent on things unrelated to criminal law violations, such as traffic control, responding to civil disputes, and administration. Even at half the total cost of policing, $63.2 billion represents a huge public investment in criminalization. As many Americans are questioning the role of police in society, they should know just how much money is available to redirect to more humane community-based responses to social problems.

Policing costs the public $126.4 billion per year, nationwide. In our report about the fiscal costs of mass incarceration to the government and families of justice-involved people, we used only half of that figure – $63.2 billion – because only about half of police work is devoted to criminal law enforcement. The other half is spent on things unrelated to criminal law violations, such as traffic control, responding to civil disputes, and administration. Even at half the total cost of policing, $63.2 billion represents a huge public investment in criminalization. As many Americans are questioning the role of police in society, they should know just how much money is available to redirect to more humane community-based responses to social problems.

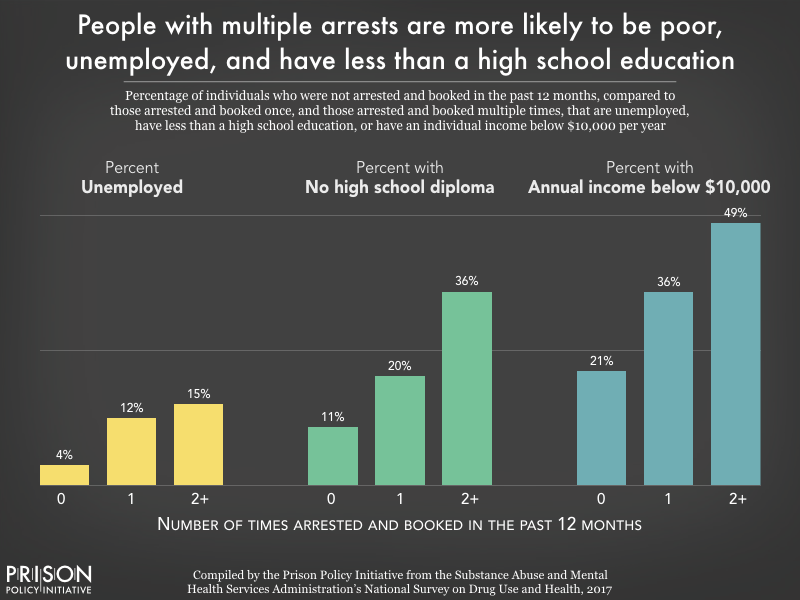

5. People who are Black and/or poor are more likely to be arrested, and to be arrested repeatedly.

People who are arrested and jailed are often among the most socially and economically marginalized in society. The overrepresentation of Black men and women among people who are arrested is largely reflective of persistent residential segregation and racial profiling, which subject Black individuals and communities to greater surveillance and increased likelihood of police stops and searches. Poverty, unemployment, and educational exclusion are also factors strongly correlated with likelihood of arrest.

People who are arrested and jailed are often among the most socially and economically marginalized in society. The overrepresentation of Black men and women among people who are arrested is largely reflective of persistent residential segregation and racial profiling, which subject Black individuals and communities to greater surveillance and increased likelihood of police stops and searches. Poverty, unemployment, and educational exclusion are also factors strongly correlated with likelihood of arrest.

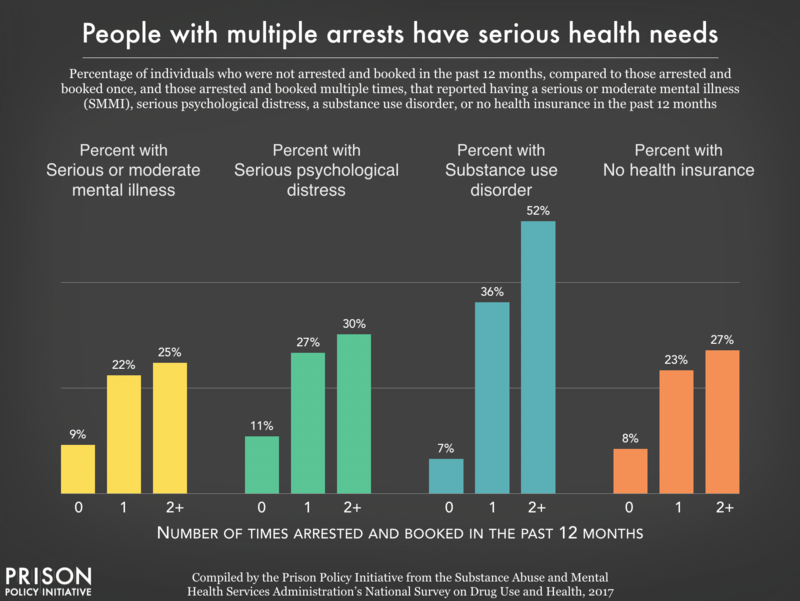

People who are arrested often have serious health needs that cannot and should not be addressed through policing or incarceration. Even a few days in jail can be devastating for people with serious mental health and medical needs, as they are cut off from their medications, support systems, and regular healthcare providers. Even worse, many people are arrested in the midst of a health crisis, such as mental distress or substance use withdrawal. History has shown that jails are unable to provide effective mental health and medical care to incarcerated people, and too often, jailing people with serious health problems has lethal consequences.

People who are arrested often have serious health needs that cannot and should not be addressed through policing or incarceration. Even a few days in jail can be devastating for people with serious mental health and medical needs, as they are cut off from their medications, support systems, and regular healthcare providers. Even worse, many people are arrested in the midst of a health crisis, such as mental distress or substance use withdrawal. History has shown that jails are unable to provide effective mental health and medical care to incarcerated people, and too often, jailing people with serious health problems has lethal consequences.

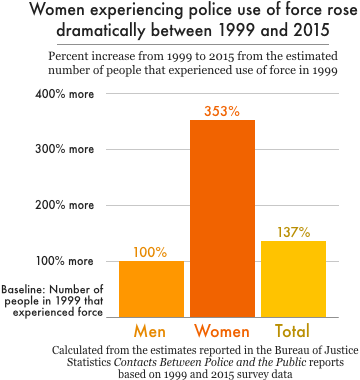

The experiences of women and girls – especially Black women and other women of color – are often lost in the national conversation about policing. But of course women, too, are subject to racial profiling, use of excessive force, and any number of violations of their rights and dignity by police. Our analysis of national data shows that women now make up over a quarter of all arrests, with an estimated 2.8 million arrests in 2018. At the same time, the use of force has become much more common among women: the number of women who experienced police use of force (about 250,000) was 3.5 times greater in 2015 compared to 1999.

The experiences of women and girls – especially Black women and other women of color – are often lost in the national conversation about policing. But of course women, too, are subject to racial profiling, use of excessive force, and any number of violations of their rights and dignity by police. Our analysis of national data shows that women now make up over a quarter of all arrests, with an estimated 2.8 million arrests in 2018. At the same time, the use of force has become much more common among women: the number of women who experienced police use of force (about 250,000) was 3.5 times greater in 2015 compared to 1999.

A closer examination of the data also reveals racial disparities in police stops, arrests, and use of force involving women. Black women are more likely than white or Latina women to be stopped while driving, and Black women are arrested 3 times as often as white women and twice as often as Latinas during police stops. Black women also report experiencing police use of force at higher rates than white or Latina women. With an estimated 12 million women per year experiencing police-initiated encounters – many of which involve searches, use of force, and other traumatizing experiences – the harms of policing to women demand more attention.

As the ACLU of Southern California and the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law report, many criminalized behaviors targeted by law enforcement are related to disability: substance use (often used as self-medication for pain and other symptoms), homelessness (an estimated 78% of people in shelters have a disability), and atypical reactions to social cues, which may be interpreted as vaguely defined crimes such as “disorderly conduct.” The Ruderman Foundation reports that in police use-of-force incidents, the media and police often blame disabled people for their own victimization, especially by characterizing disabled people of color as “threatening” and “refusing to comply.”

The frequent use of police as first responders to individuals in crisis only compounds these problems. Too often, officers who are called to help individuals get medical treatment end up shooting them instead. Public funds should be redirected to community health providers to handle mental and physical health crises, rather than trying to meet this critical need with militarized police forces, who sometimes receive little training on crisis response or de-escalation.

9. Police treat Black Americans with less respect.

A Stanford University analysis of police bodycam footage from nearly 1,000 vehicle stops substantiates what Black Americans already know: police officers treat Black people differently than they do whites. This study, discussed in our briefing, finds that “police officers speak significantly less respectfully to black than to white community members in everyday traffic stops,” and that this happens irrespective of officer race, severity of the infraction, and outcome of the stop. These findings lend important context to the racial disparities observed in police encounters.

10. State and federal law enforcement practices target poor Black and Latinx residents.

Separate reports focusing on policing in Chicago highlighted two law enforcement strategies justified as ways to protect communities – drug stings and asset forfeiture – that facilitate widespread targeting of low-income communities of color. Federal agents from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) arranged drug stings that set up fake drug stash houses and lured people into committing new crimes. But they didn’t single out just anyone: At least 91% of the time, agents targeted Black and Latinx people. Columbia professor Jeffrey Fagan’s analysis found no statistical explanation for this except disparate racial treatment. A District Court judge described these cases as “ensnaring chronically unemployed individuals from poverty-ridden areas.”

Meanwhile, Cook County police conducted 23,000 seizures of assets connected to civil and criminal cases, a practice that is supposed to disrupt major illegal drug trades. But an analysis by Reason and the Lucy Parsons Lab showed that police officers were often taking petty property and the lowest-value seizures (valued under $100) were clustered in predominantly poor and Black communities on Chicago’s South and West Sides. These examples illustrate that at every level, the “war on drugs” functions as a war on communities of color.

The “services” offered by jails don’t make them safe places for vulnerable people

Even in the best of times, jails are not good at providing health and social services.

by Alexi Jones, March 19, 2020

With jails considering major policy changes as part of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, we’re seeing a troubling question from allies with a little less experience on criminal justice issues: Given that jails provide valuable social services, wouldn’t it be bad to release people who need services? Aren’t the homeless, the mentally ill, or people with substance use disorders better off in jail?

In a word: No.

The longer answer is that even in the best of times, jails are not good at providing health and social services. Although local jails are filled with people who need medical care and social services, jails have repeatedly failed to provide these services. As a result, many people end up cycling in and out of jail without ever receiving the help they need. For example, even though a disproportionate number of people in jails have mental health disorders, jails have repeatedly failed to provide adequate mental healthcare. People with mental health disorders are often put in solitary confinement, have limited access to counseling, and not checked on regularly due to staffing shortages. The tragic result of these failures is that suicide is the leading cause of death in local jails.

Similarly, jails consistently fail to provide adequate medical care to incarcerated people. Notably, although two-thirds of people in local jails have a substance use disorder, most jails and prisons refuse to provide medication assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid use disorder—the gold standard for care. Moreover, substandard healthcare has had lethal consequences. For example, CNN recently published a scathing investigation into WellPath (formerly Correct Care Solutions), one of the country’s largest jail healthcare providers. They found that WellPath provides substandard healthcare that led to more than 70 preventable deaths in local jails between 2014 and 2018.

It’s absolutely true that people in the criminal justice system have a lot of ignored needs. But we shouldn’t misconstrue the “services” offered in jails as reasons to keep people confined in what are always harmful conditions. Given that many people in local jails have health conditions that make them especially vulnerable to this new coronavirus, and simple precautions like social distancing are nearly impossible behind bars, it is vital that we release anyone from jail who doesn’t need to be there. For many, it will be a matter of life or death.